Kelmscott Chaucer lives in the treehouse. If you walk in the front door of Temple University's Paley Library, you see what appears to be a rickety elevated fort built against the back wall of a large atrium. The building is standard issue 1960s concrete and glass institutional style, but the treehouse is a friendly wooden structure that looms over a bank of computer terminals in the atrium below.

Kelmscott Chaucer lives in the treehouse. If you walk in the front door of Temple University's Paley Library, you see what appears to be a rickety elevated fort built against the back wall of a large atrium. The building is standard issue 1960s concrete and glass institutional style, but the treehouse is a friendly wooden structure that looms over a bank of computer terminals in the atrium below.My favorite person at Temple lives there. Thomas Whitehead, the head of Special Collections, is an ex letterpress guy who presides over the best collection of artists' books in the city. Going into the special collections room in the treehouse is like sneaking into the back room of a museum: there are amazing things everywhere you look: illuminated manuscripts, old woodblocks, books the size of your fingernail and the size of your torso. Not to mention sci-fi posters and pieces of type with the entire, apparently, Lord's Prayer carved on their tiny tops.

I see Thomas Whitehead once or twice a year when I take people to look at artists' books. The man has and knows everything. He shows us artists' books made of latex, soap, quilts, bras, and glass. He tells us to sniff the beautiful book from Vietnam that smells of the tobacco leaves that are used in the paper, and he once got out a can opener and opened one edition of the two books-in-a-can he'd bought so we could see what was inside. He's got a great collection of rare books, sci-fi and propaganda posters, as well as political literature from the sixties. And it's his job. He's up in the treehouse, preserving the culture.

Today I went to a presentation he gave on the Kelmscott Press Chaucer. This is a book by William Morris' Kelmscott Press, and it's insanely gorgeous.

This is William Morris. He also wrote books himself, like this one, The Story of the Glittering Plain or The Land of Living Men.

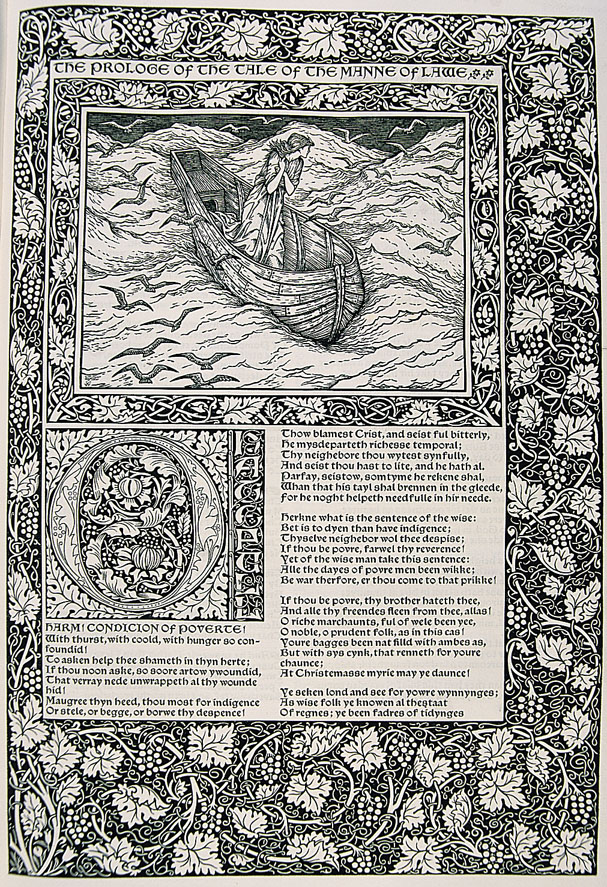

The Chaucer is illustrated by Edward Burne Jones, a Preraphaelite painter, with initials and borders designed by Morris. There's plenty of information about it on the web, but I thought I'd post some pictures it in case anyone has not had the good fortune to run across it yet. Or wants to know what I want for Christmas.

(Click the image above to enlarge.)

Every illustrated page has these incredible borders, and the type is hand-set with beautiful elaborate initials.

(Click to enlarge)

It's in English, and lots of libraries have them. If you live in San Francisco you can go to the public library's rare book collection and just check it out for a few hours. They give you white gloves and watch you to make sure you're not taking out your scissors or anything, but you can sit there and just read it. You could come back every week and read a chapter. (I asked. And then, sadly, I moved to the East Coast.)

(Click to enlarge)

The Kelmscott Chaucer is an amazing testament to, among other things, the value of work.

These are the printers working on the Chaucer.

I've been working on another very slow, large drawing lately, and I'm really enjoying it. I was thinking today, as I took five hours to shade in the ends of two banners and some drapery, that I really love work. That work in itself has become a value to me. I don't mean that any work is its own reward- any ex-temp knows that's not true- and it's not that I actually enjoy every moment of working. Nor do I count my job as work. But work directed towards something one loves is a powerful thing. Work on art opens up artistic possibilities. I feel, lately, like it's possible to access the kinds of visual gestures and bravado that were common in other eras if I remove the pressure to make my art quickly. It might be that given enough time, I really can do fake Victorian engravings with my ballpoint pen.

It's tremendously liberating to commit to that endeavor- to work much longer than I usually would on making something look good, even if that seems fantastically inefficient. It feels rather revolutionary too- there's something neat about putting so much effort into transforming a single piece of paper with the disposable pen I bought at Office Depot.

If I give myself five hours to spend working on carefully shading my drapery, I can get a really good looking image. My image looks old fashioned, and that's partly because I'm giving the piece the time that people used to put behind their work. I don't mean thinking time. I mean hand on the paper time. Work.

It's not a new impulse. But I think it's a good one.

There are some great large Morris images here, courtesy of one Florence Boos at the University of Iowa, who also happens to be president of the U.S. chapter of the Morris Society, and there's also a good article on the Kelmscott Press Chaucer here.

No comments:

Post a Comment