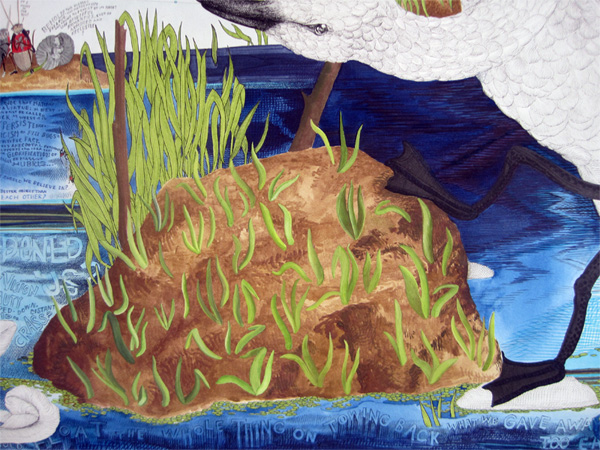

I just got a new piece posted on my website- it's called Pull, and I'm quite happy with it. You can see it better by clicking the link above and going to the details, but I thought it was worth a blog post to write down some of the text in the image that's hard to see on the web.

A friend of mine who is a genius artist asked me what all the swans in my work were about recently, and I answered without any hesitation, "Beauty."

"Yeah, they're the thing we're supposed to think is beautiful," she said, "they're like the stand-in for beauty."

"For me," I said, "they're like chaotic, unrestrained beauty- visceral, like it or not, popular beauty."

And then I'm pretty sure she said, "They are beautiful, but they're goona eatcha."

I may just hope she said that.

Because that's what I'm interested in lately. I'm interested in the way that art constructs an elite around ideas of aesthetic difference, and the ways that commonplace beauty gets excluded from that dialogue. There's a lot of stuff about that in this piece.

The main text along the top of the piece says, "Placing my trust in the..."

...ruthless advance of spring."

The word advance looks like this:

My grandfather worked in oil fields, and I was thinking of old wooden oil rigs. There's some tiny text above the rig that says, "Flowers every year regardless of my bad attitude."

Speaking of which, this spring I went to my high school reunion and had a really wonderful time. I went to a great high school and was stunned to see that several of my classmates do seem to have gone on to run the world. Lovely people. Great education. But in true bad attitude fashion, I have bitten the hand that fed me and given a cockroach on this piece my high school sweater.

Along the left side of the piece there are a few big text sections. There is a floating woman saying, "Our ideals have stolen the wrong weaknesses."

When I was drawing that text I was thinking about how idealistically we have turned away from our weaknesses for aesthetic pleasures. Artists can be dumb about which kids of beauty they will admit to- we like our beauty separate from commercial culture. That's idealistic, but in reacting against exploitable images I think we've reacted against common experiences- we've thrown the baby out with the bathwater. I think we need to be able to look at swans, sunsets and each other without feeling like we're being freaking ironic. I kept thinking about that idea here:

The text in the lake says, "Has art abandoned us, left us distrustful of any vision of what we love, afraid that beauty in all but the most virtuously strict, stripped down, distant form is somehow shameful, stupid or crass?"

People ask me a lot about the Victorian thing I'm doing. It's partly about the way that I think we construct art world beauty now- I think that the prissiness that we have as a culture about acceptable forms of high culture aesthetics is very similar to the kind of prissiness that Victorian men had about women. There's a way in which I totally understand the Victorian male vision of sexuality. It's as if they think they are very logical, very serious, very smart, very known, and very dreary. So they organize and collect and categorize everything. They dress in black. And they think that sexuality and love is totally mysterious and out of control, so the women in that era are both caged and decorated- their clothes and position in society embody a fear of and longing for the other that is all about controlling the uncontrollable nature of desire. They cage it, decorate it, and demean it- make it seperate from power or any meaningful negotiation in society while making sure that they revere it in its pure form- Victorian men were all about the cult of the mother, and virtues were female...I think we do that with aesthetics, at least in high art.

We like disembodied beauty, and if we talk about aesthetic beauty that we can all access directly, there's an urge to either make sure it's radically logical, disembodied from normal visual experience and placed into a conceptual framework or, if it does reference something that's not radically distant from the average citizen's visual experience, to somehow demean it. I was once told (no kidding) by a hilariously accented dealer that "we in New York like our art with an edge..." I think sometimes that edge is the knife that cuts between the classes- there's a lot about class that explains why it is utterly sophisticated to make something that does not open itself up to common experience at all..

Sometimes I think that abstraction was a perfect American art movement, because it let us take our proto-Victorian impulses out on beauty- we could strip it of all attachment to politics, to mortality, to ourselves and each other and make it pure. I love abstraction- some of my best friends- but I also am interested in how truly radical it is to draw the figure these days. It's absurd. Art people often think that I must be stupid because I draw people's bodies. It's as if looking at each other has become a symbol of ignorance. That's what I mean about our ideals stealing the wrong weaknesses, too.

We are afraid of embodied beauty- we're afraid of beauty that is tied to people, to things that we can lose....Going to Rome, being steeped in all that Donatello and the baroque made me feel that. It's much easier to be a fat aging American in front of a Rothko than it is in front of that statue of Danae.

Our art of the last half century seems to me to be an art emphatically NOT of the body. Not the body, the story, the place, the family- it's an art of the mind, serious, logical, cerebral, dressed in black...I want to make the other art.

I want a lot of things. In the left hand corner there's a little self portrait in a flower petal boat. Underneath it along the whole bottom of the piece it says, "As if aesthetics..."

were a boat

we could float the whole thing on...

towing back what we gave away too easily."

There are also, in case that's all too obscure, some editorial bugs.